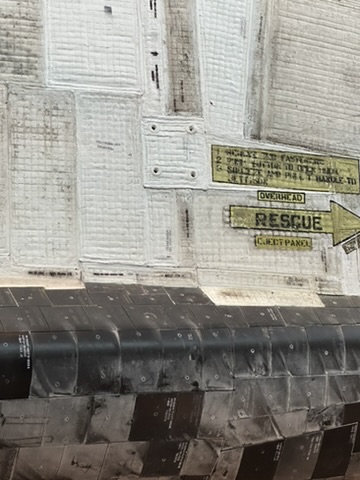

A few weeks ago I was in Northern Virginia just outside of Washington D.C. In our time up north, I went to the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, which displays thousands of aviation and space artifacts, including the Space Shuttle Discovery and a Concorde, in two large hangars. Seeing the shuttle up close led me to have more questions about how these massive spacecrafts are built and why. As I looked at the tiles on the underside of the shuttle—distressed with varying colors—I found myself wondering what had happened to the ship and the purpose of these clearly used tiles.

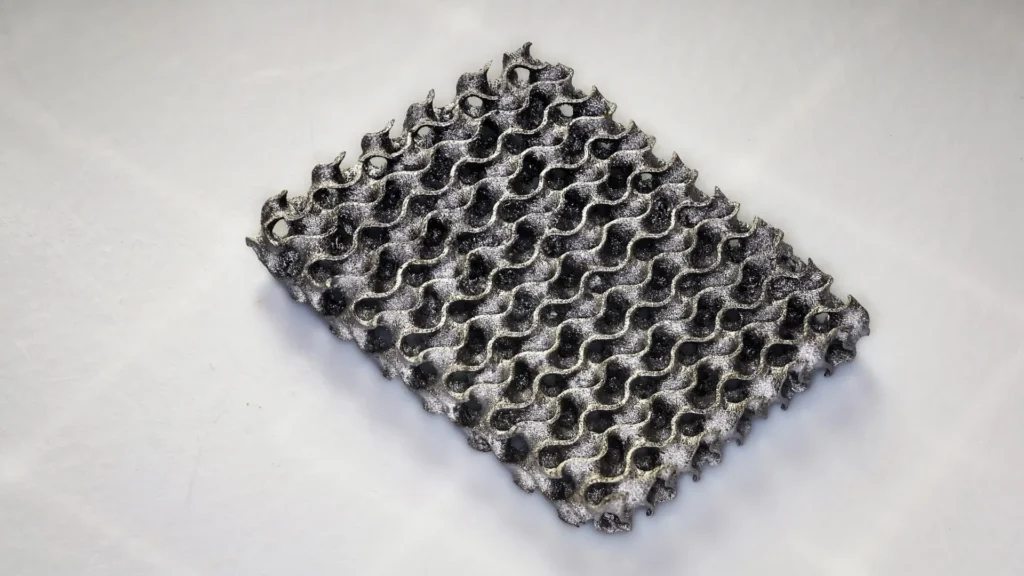

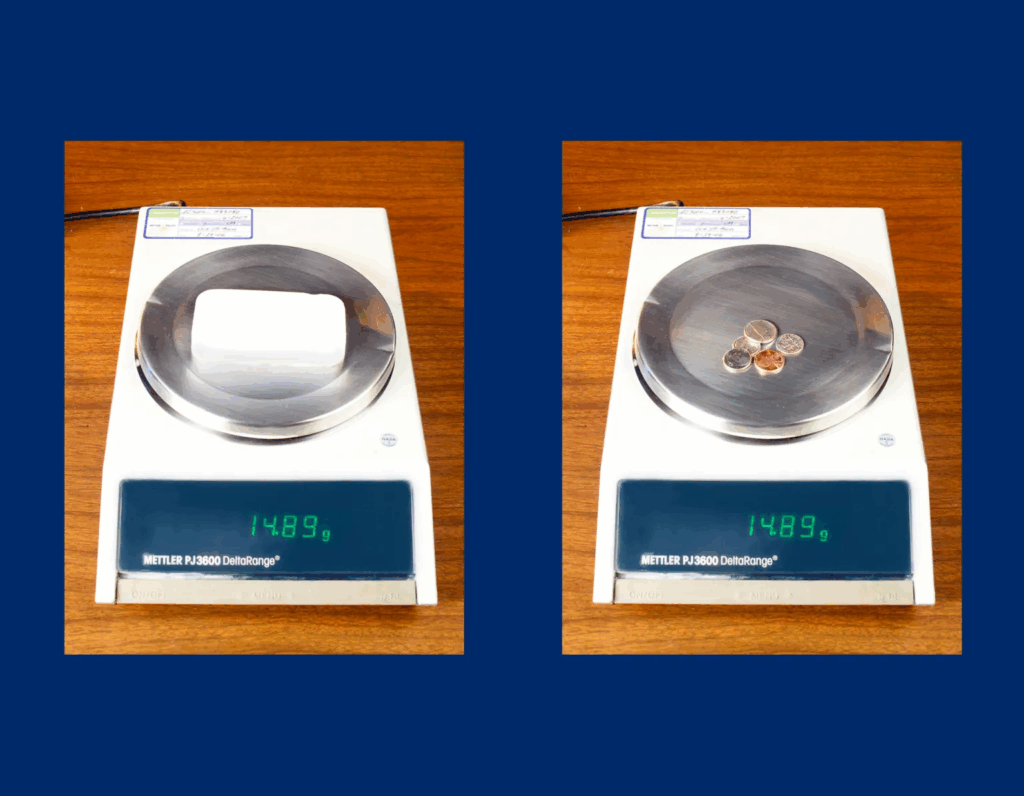

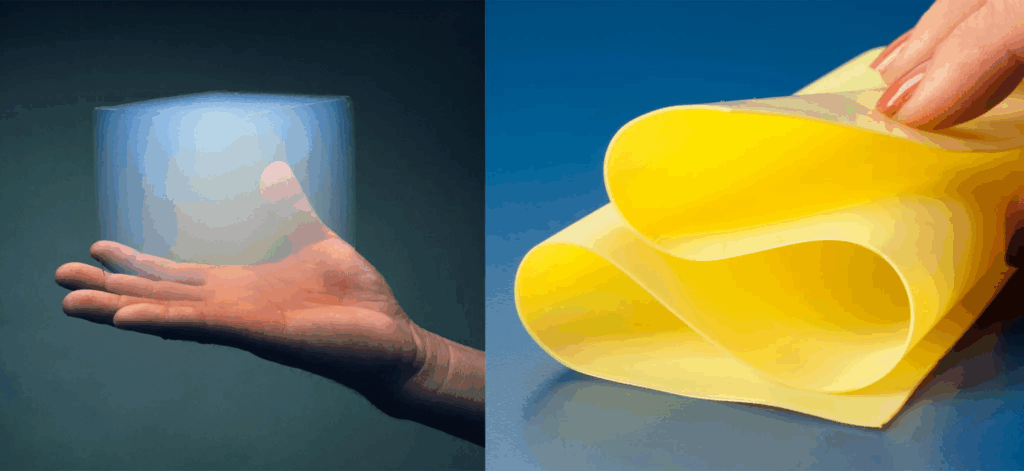

Those weathered tiles were part of Discovery’s Thermal Protection System (TPS), one of the most critical engineering features of the entire shuttle. Each tile was made from a lightweight silica-based ceramic designed to withstand temperatures exceeding 2,300°F (1,260°C) during reentry, while keeping the aluminum structure beneath cool enough to touch. No two tiles were exactly alike; each was custom-shaped and hand-installed. The discoloration and scarring I noticed were evidence of repeated trips through Earth’s atmosphere. In fact, Discovery—the most-flown shuttle in NASA’s fleet—completed 39 missions, including the return to flight after the Columbia disaster, meaning its tiles tell a visual history of stress, heat, and repair. Every darkened edge and mismatched square represents the brutal physics of reentry and the remarkable materials engineering that allowed astronauts to come home safely every time.

References

Jenkins, D. R. (n.d.). tps. Www.nasa.gov. https://www.nasa.gov/history/sts1/pages/tps.html